Introduction

Before diving into the somewhat complex world of Artificial Intelligence (AI), let’s first consider what intelligence means from a human perspective. Judo, as a martial art, serves as a good—though not an obvious—example. I trained in judo for over 20 years. During that time, I learned which throwing techniques to use to take down an opponent efficiently by leveraging their movement energy and reactions. But how did I learn that? Through a supervised training process, where our coach first taught us the throwing techniques and the situations in which they work best. Then, we practiced them ourselves. Mastering these techniques requires thousands of repetitions before achieving perfection. Ultimately, timing and reaction to the opponent’s movements play a significant role in determining whether a throw is successful or not. After mastering several throwing technics, I was capable of apply them in the situation not necessarily to seen before.

How does this relate to Artificial Intelligence (AI)? AI is a broad term encompassing solutions that aim to mimic human brain functions. A subset of AI is Machine Learning (ML), which enables systems to make decisions based on input data without being explicitly programmed for each scenario. The driving force behind this capability is Deep Learning (DL), which utilizes Deep Neural Networks (DNNs). The intelligence of these networks resides in thousands of neurons (Perceptron) and their interconnections which together form a neural network.

Training a Neural Network to perform well in its given task follows the same principles as training a human to execute a perfectly timed and well-performed throwing technique, for example. The training process takes time, requires thousands of iterations, and involves analyzing results before achieving the expected, high-quality outcome.When training Neural Networks, we use a training dataset that, in addition to input data, includes information about the expected output (supervised learning). Before deploying the network into production, it is tested with a separate test dataset to evaluate how well it performs on unseen data.

The duration of the training process depends on several factors, such as dataset size, network architecture, hardware, and selected parallelization strategies (if any). Training a neural network requires multiple iterations—sometimes even tens of thousands—where, at the end of each iteration, the model's output is compared to the actual value. If the difference between these two values is not small enough, the network is adjusted to improve performance. The entire process may take months, but the result is a system that responds accurately and quickly, providing an excellent user experience.

This chapter begins by discussing the artificial neuron, and its functionality. We then move on to the Feedforward Neural Network (FFNN) model, first explaining its layered structure and how input data flows through it in a process called the Forward Pass (FP). Next, we examine how the FFNN is adjusted during the Backward Pass (BP), which fine-tunes the model by minimizing errors. The combination of FP and BP is known as the Backpropagation Algorithm.

Artificial Neuron

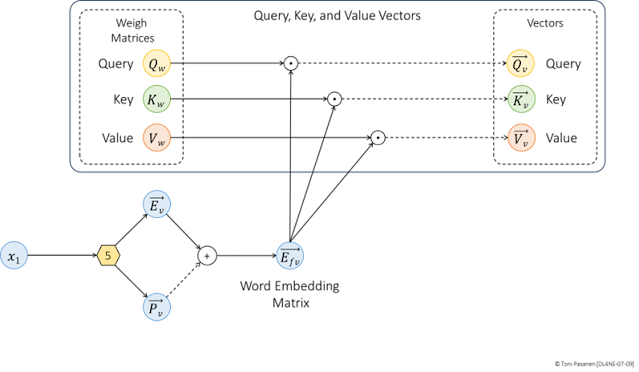

An artificial neuron, also known as a perceptron, is a fundamental building block of any neural network. It functions as a computational unit that processes input data in two phases. First, it collects and processes all inputs, and then applies an activation function. Figure 1-1 illustrates the basic process without the complex mathematical functions (which I will explain later for those interested in studying them). On the left-hand side, we have a bias term and two input values, x1 and x2. The bias and inputs are connected to the perceptron through adjustable weight parameters: w0, w1, and w2, respectively. During the initial training phase, weight values are randomly generated.

Weighted Sum and Activation Function

As the first step, the neuron calculates the weighted sum of inputs x1 and x2 and adds the bias. A weighted sum simply means that each input is multiplied by its corresponding weight parameter, the results are summed, and the bias is added to the total. The bias value is set to one, so its contribution is always equal to the value of its weight parameter. I will explain the purpose of the bias term later in this chapter. The result of the weighted sum is denoted as z, which serves as a pre-activation value. This value is then passed through a non-linear activation function, which produces the actual output of the neuron, y ̂ (y-hat). Before explaining what non-linearity means in the context of activation functions and why it is used, consider the following: The input values fed into a neuron can be any number between negative infinity (-∞) and positive infinity (+∞). Additionally, there may be thousands of input values. As a result, the weighted sum can become a very large positive or negative value.

Now, think about neural networks with thousands of neurons. In Feedforward Neural Networks (FFNNs), neurons are structured into layers: an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. If input values were only processed through the weighted sum computation and passed to the next layer, the neuron outputs would grow linearly with each layer. Even if we applied a linear activation function, the same issue would persist—the output would continuously increase. With a vast number of neurons and large input values, this uncontrolled growth could lead to excessive computational demands, slowing down the training process. Non-linear activation functions help keep output values within a manageable range. For example, an S-shaped Sigmoid activation function squeezes the neuron’s output to a range between 0 and 1, even for very large input values.

Let’s go back to Figure 1-1, where we first multiply the input values by their respective weight parameters, sum them, and then add the bias. Since the bias value is 1, it is reasonable to represent it using only its associated weight parameter in the formula. If we plot the result z on the horizontal axis of a two-dimensional chart and draw a vertical line upwards, we obtain the neuron’s output value y at the point where the line intersects the S-curve. Simple as that. Naturally, there is a mathematical definition and equation for this process, which is depicted in Figure 1-2.

Before moving on, there is one more thing to note. In the figure below, each weight has an associated adjustment knob. These knobs are simply a visual representation to indicate that weight values are adjustable parameters, which will be tuned by the backpropagation algorithm in case the model output is not close enough to expected result. The backpropagation process is covered in detail in a dedicated chapter.

Bias term

ReLU Activation Function

- If z>0, return z.

- If z≤0, return 0.